Farming, Soldiering & Cheffing: Mark’s Story

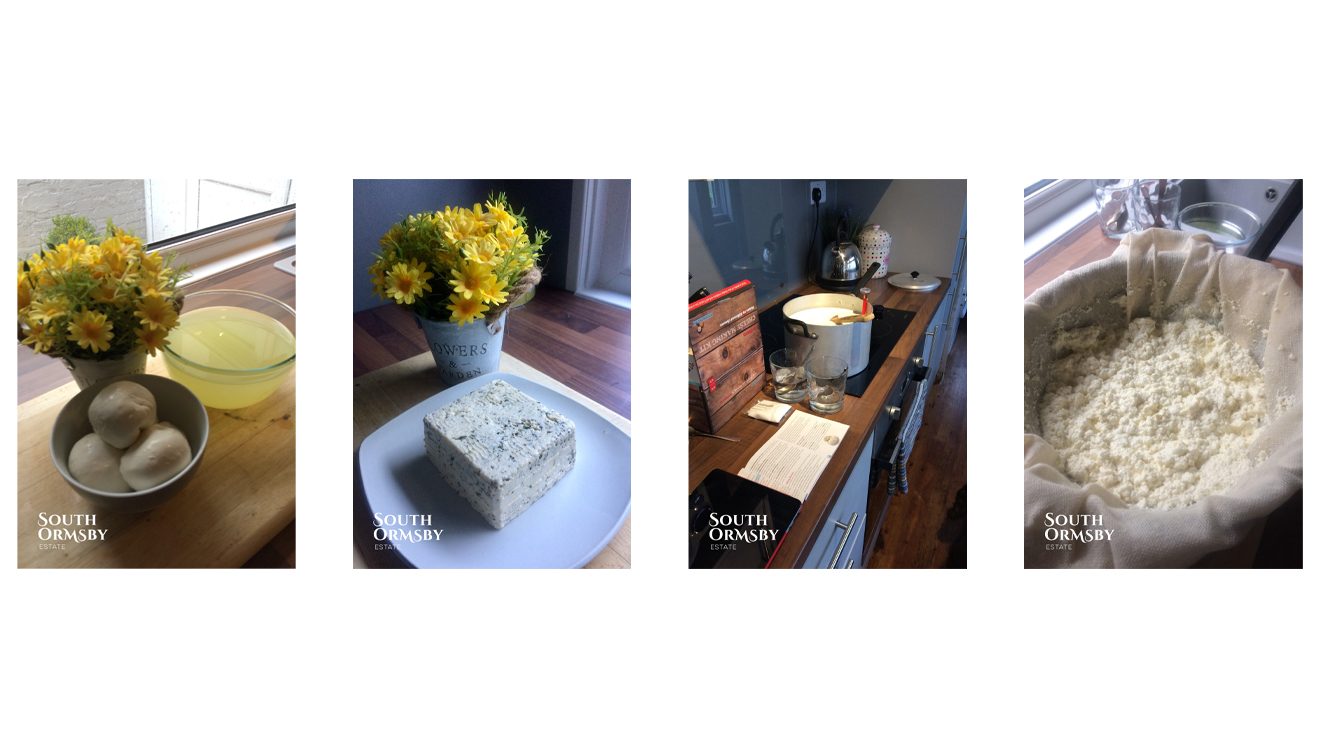

Veteran chef Mark Vines, 49 years, is South Ormsby Estate’s new cheese creamery operator. Hailing from Louth, Mark comes from farming stock and brings a love of good food and traditional agriculture to his exciting new role.

“I was born in Louth and grew up in Burwell and Tathwell,” said Mark. “I’ve got a multi-generation farming background. I remember my granddad driving through the village in an old-fashioned, open-cab combine harvester with a white hankie over his mouth to keep the dust out. My other granddad was a shepherd who still used working shire horses well into the 1980s. When I was five or six, they really towered over me and I had to jump up to grab their reins.

“I grew up with the farming life. We didn’t go away during the holidays as dad would be on the land, working. As a kid, I helped with lots of jobs, from planting trees to weeding sprouts, and from trimming kale to beating for shooters. I did everything but drive the tractor. My dad’s farm manager had a progressive attitude in all sorts of ways. Where the land had been completely stripped for crops, he wanted to put nature back in the picture. He planted tens of thousands of trees he’d never get to see mature. Every year, the farmers organised ditch-clearing between themselves to make sure the land could drain effectively.